Sometimes two statements are both truisms, but these truisms may clash. As with these two:

“We need to be agile”

“We need evidence-based change”

Because when we think of agility, we think of fast change and when we think of evidence-based change, we think of thinking before we start.

Where can they meet after all?

Evidence-based change

In order to bring both worlds together, it is necessary to go back to the function of substantiation in change processes. To make this function clear, I will give you three statements by scientists:

Of four anti-bullying methods, the second gives the best results.

This vaccine protects people in 90% of cases

This new way of working leads to 40% shorter turnaround times

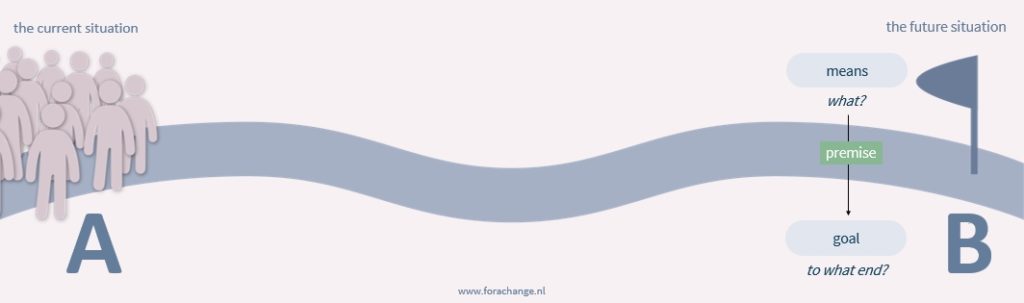

With their statements, these scientists show that they have examined the premise between a means and an end. The premise is the central assumption that lies beneath the change; between what you want to develop or introduce and the effect you want to achieve with it (Mars, 2016, page 31).

Between an anti-bullying method (means) and the well-being of pupils (ends)

Between a vaccine (means) and the degree of protection (ends)

Between a new way of working (means) and speed (end)

When scientists analyse how the means works in a large sample of situations, they help us to estimate how it will also work in our own situation. This foundation protects us from solutions that seem like a good idea when we think of them, but that do not stand the test of complex practice.

Evidence-based change is our weapon against mirages, whimsy, quackery and hypes.

Means and end confusion

Now we can also face an important cause that hinders evidence-based change. Evidence presupposes the existence of a means and an end. And in too many changes, the signpost only shows a means. The real goal has been relegated to the background (and so has the urgency, but that is another blog). People still know what they are building or implementing, but no longer what they want to achieve with it.

A lack of evidence-based change is then a symptom of a deeper problem: of means and end confusion. This common pitfall is doubly tragic: due to a lack of direction, these changes will fail, while the mechanism to find out that they are failing is lacking.

Agility

But what about the proposition that in times of continuous change, we must be above all agile? Because if you have to wait until an idea has been scientifically validated, competitors have already overtaken you three times. Or the problem you want to solve has only gotten worse. And in a fluid world, ends and means gradually take shape. Can you examine your assumptions of a change that is still crystallising?

The answer is a resounding yes! An ambition to be agile can never be a reason to abandon substantiation. After all, we call not questioning your assumptions tunnel vision. Then you are agile, but your twists and turns take you nowhere.

Your own substantiation

So what do you do if your idea has not been scientifically validated, but you still think you are on to a solution to an urgent problem? Then you need to start collecting your own evidence. This means putting three items firmly on the agenda throughout the process:

- What you want to achieve

- How far away you are from your goal

- What signals you are getting that the means is bringing you closer to your end

Applicability

The three fixed topics of discussion apply just as well if your idea has already been scientifically researched. Because every situation is different. In your situation, other variables may come into play than those included in the research. You may pursue secondary objectives that fall outside the scope of the research hypothesis. Your situation may be one of the 20% of cases in the study that shows that the means is effective in 80% of cases. The art of evidence-based change is to assess sound research in a sample of countless situations for its applicability to your situation.

So?

You combine agility and science when you make full use of the geniuses in science, and you also keep your own head.

Annemarie Mars, April 2021